In the Driver's Seat with Lisa: Connecting the Disconnect

By Lisa Day, Food Rescue Coordinator

Farming contributes more than $130 billion to the US economy and yet farmers make up only 1.3% of the entire US workforce. Compared to the 1840s, the amount of people working in agriculture went from 70% to just under 2% today. With such a steep decline in agricultural work, agricultural literacy throughout the country has also declined, and to quite dismal levels. Statistics like this can help us understand why it’s possible for 7% of Americans to believe chocolate milk comes from brown cows. Or that a majority of Americans don’t know where their food comes from, or what staples like sugar, grains and rice look like before they’re packaged. Or even that cheese comes from cow’s milk.

Throughout the years, what has become increasingly evident is just how vast the disconnect is between humans and nearly everything else – between us and our food, our planet and even each other. However, as everything from consumer opportunity to available technology to social media platforms has continued to expand tremendously, it is easy to see how this disconnect persists. With such an expansive system and a lack of transparency, it is difficult for the average consumer to know where any part of the production process begins or ends. We are presented with countless “products” that have been through countless processes and yet we typically only see the end result. We see none of the energy, resources, and time that went into the car, bookshelf, or even apple we just bought.

These sorts of consumer/product disconnects are everywhere. Just think of the things in your own home. Where did it come from? What materials went into it? How it was put together? Who put it together? A lot of us don’t know. And while the buy local and farm-to-table movements have worked to bring the consumer closer to the things they buy, unless we can confidently answer these types of questions, a disconnect still persists. The one that I want to talk about now, is food.

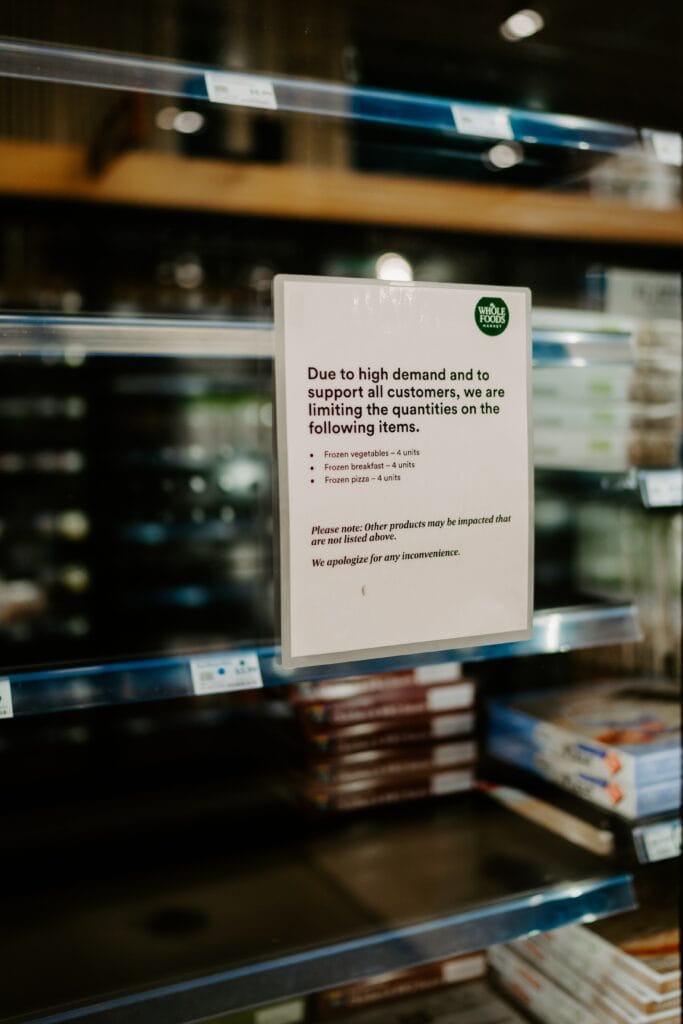

In the past few months, we have all witnessed widespread panic buying, long lines to get into grocery stores, and countless empty shelves. This was the first time in my life that I had ever seen stores so stripped of their most basic staples. As a Food Rescue Coordinator, I rescue food from at least 5-7 different stores per day and when panic buying was in full swing, they were all struggling. Day after day, consumers were buying out all of their eggs, flour, meat, and of course toilet paper. With so many people overwhelming the system, their collective actions unfortunately left us with fewer donations and much less to give to the community. This reminded me of something I learned about in school called the “Tragedy of the Commons.”

The original idea of the Tragedy of the Commons used an analogy of ranchers grazing their cattle on a shared, common field. Logically, each rancher would want to add livestock in order to increase profits. This increase, however, would benefit the rancher alone who was still sharing the “commons.” With each rancher increasing their livestock, eventually overconsumption would ruin the field and none would be able to graze it. The general takeaway was basically that while people share a “commons,” (i.e. food, energy, resources), there is a tendency for the individual to act in their own best interest. However rational this may be, this manner of thinking logically instead of collectively, ultimately leads to overconsumption and depletion of resources for the rest of the community.

Today, our “commons” are much bigger than the fields in that analogy. One could argue they are so great that we don’t even know who our neighboring “ranchers” are. And as a result, we rarely see the effects of our buying decisions or how they affect resources and other people. In regards to the environment and climate change, people often use the Tragedy of the Commons to explain why more sustainable action isn’t taken at an individual level. The argument is that as a collective, we know how our actions (such as driving cars, wasting food, buying single-use plastics and bottled water, etc.) all have a negative impact on our environment; however, each individual action is so small that it barely contributes to the collective impact, so maybe it doesn’t really matter. Regrettably, if everyone adopts this way of thinking, the collective impact becomes much greater and more negative as a whole. I think this is evidence that everything we do at the individual level does indeed have an impact on our world.

In the last decade, there has been a significant increase in mindful consumerism and more eco-friendly living. Many people are now seeking food, clothing, and goods from local sources or are making their own, and therefore decreasing their footprint. However, while being resourceful and reducing waste are the cornerstone to minimalist/eco-conscious/buy local movements, in the midst of the current pandemic this type of lifestyle might be new to a lot of people.

For so long, we have been living in a culture of excess where anything and everything has been readily available to us, to the point where consumers may feel a sense of entitlement to this availability and may think it outrageous when stores don’t have a certain product on hand. For this reason, stores are often compelled to order (and then waste) much more than necessary in order to keep their shelves constantly stocked. This acquired desire for excess, coupled with a disconnect to our food, is why 40% of all food produced in the US goes to waste while 12% of the population remains hungry. It is why organizations like Lovin’ Spoonfuls can even exist.

For the last 10 years, we have been fighting food waste and food insecurity through food rescue. However, the ability to “rescue” food is only possible when food waste is present. What is disheartening is that also present are food insecurity and diminished food access. We have an overabundance of 133 billion pounds of food that gets thrown away while 1 in 8 people go hungry every night, a fraction that has only increased in response to COVID19. These are problems that have been around long before the current pandemic, however now more than ever, are we seeing so clearly the systematic failure of our food system – as one that focuses more on maintaining abundance, than actually feeding people. It is clear that what is required is systemic change, but also that we can adapt and are capable of systemic change.

Right now, most of us are experiencing a sense of having to “make do” with what we have. And in doing so, we have been able to reconnect with a lot of things – we’re rediscovering the art of cooking, figuring out what our hobbies are, and contemplating how we genuinely want to spend our lives. Along with demonstrating our capability of systemic change in regards to fighting climate change, I think this may be the biggest silver lining to the coronavirus – the development of a more conscious way of viewing the world, life and everything it offers. What we are seeing now is proof that humans can indeed function and even thrive with less. We can be resourceful, we can save more and waste less, we can grow our own food, and we can treat our fellow humans and our environment with respect. I hope when the world recovers from this pandemic, that we will remember this time and move forward with a continued sense of connection to ourselves and our capabilities, to our food and our environment, and to each other.

If you’d like to learn more about agriculture and agricultural literacy, the American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture has a lot of great resources and teaching materials!

CIAT also has some fun interactive maps showing where food comes from and where it goes.